The Boy Scouts of America in three parts:

Part I – Being a Boy Scout | Part II – Origins | Part III – Organization

There are many stories about how the Boy Scouts came into existence: Unknown Scouts on foggy London streets, clubs organized for wayward boys, or alternatives to a growing urban way of life. What is for sure is the zeitgeist or spirit of the age in which the idea of the Scouts emerged.

In short, as the middle class began to take shape in early 20th century and families moved from rural farms to urban city, there was a growing concern among some about the loss of patriotism and individualism instilled in young people. Part of that drive was a sort of early social welfare that included programs to provide physical, mental, and spiritual development for those who wanted them. The YMCA was an early promoter of these reforms and an early proponent (and organizer) for the Scouts which in quick turn, in 1910, incorporated as the Boy Scouts of America with the express purpose of teaching boys “…patriotism, courage, self-reliance, and kindred values.” The Scouts first Director, Edgar Robinson was a former YMCA administrator who brought his skills and expertise and applied them to the newly formed Boy Scouts.

Read a complete time-line of the Early Scouts formation.

The prospect of a National Boys movement as such even garnered a national Federal Charter by Congress in 1916 as both a Patriotic and National organization.

What the scouts captured was an ideal citizen, a compassionate, reverent, and committed member. The ideal of this is codified in its mission statement which has gone through some evolution from its origins to present day.

1936 – “Each generation as it comes to maturity has no more important duty than that of teaching high ideals and proper behavior to the generation which follows.”

2008 – “to prepare young people to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law”

Two notable predecessors of the Boy Scouts in the United States were the Woodcraft Indians started by Ernest Thompson Seton at Cos Cob, Connecticut, in 1902 and the Sons of Daniel Boone founded by Daniel Carter Beard in 1905 at Cincinnati, Ohio. A more pronounced source came in 1907 from the founding of the Scouting movement in England by British General Robert Baden-Powell who used elements of Seton’s works to create Several small local scouting programs for boys.

Two notable predecessors of the Boy Scouts in the United States were the Woodcraft Indians started by Ernest Thompson Seton at Cos Cob, Connecticut, in 1902 and the Sons of Daniel Boone founded by Daniel Carter Beard in 1905 at Cincinnati, Ohio. A more pronounced source came in 1907 from the founding of the Scouting movement in England by British General Robert Baden-Powell who used elements of Seton’s works to create Several small local scouting programs for boys.

Wikipedia says of this inspiration:

“In 1909, Chicago publisher W. D. Boyce was visiting London, where he encountered the Unknown Scout and learned of the Scouting movement. Soon after his return to the U.S., Boyce incorporated the Boy Scouts of America on February 8, 1910. Edgar M. Robinson and Lee F. Hanmer became interested in the nascent BSA movement and convinced Boyce to turn the program over to the YMCA for development in April 1910. Robinson enlisted Seton, Beard, Charles Eastman and other prominent leaders in the early youth movements. In January 1911, Robinson turned the movement over to James E. West who became the first Chief Scout Executive and Scouting began to expand in the U.S.”

It makes for an interesting Masonic aside to find the parallels between Masonry and Scouting, yet only a few concrete connections to American Freemasonry can be found that have carried to present day.

First of those connections being through Daniel Carter Beard and his Sons of Daniel Boone, of which a notable Masonic award exists today for the support of Freemasonry and Boy Scouting aptly called the Daniel Carter Beard Masonic Scouter Award which is presented to any Master Mason who has made significant contributions to youth through Scouting. This is a selective award, the purpose of which is to recognize the recipient’s outstanding service to youth through the Boy Scouts of America.

A second, and perhaps more prevalent in the daily operation of lodge and troop, is the National Association of Masonic Scouters which works to foster and develop support for Boy Scouts of America by and among Freemasons while upholding the tenants of Freemasonry.

A third connection is a bit more at the root of the early organization. Following Robinson as director of the newly formed BSA, James E. West was appointed director. West also happened to be a Freemason (complete records of his lodge affiliations have been a challenge to find).

Freemasons for Dummies blog recently reported on the Lodge opened at the 100th Jamboree in conjunction with Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4. Said of the event: The meeting was simply amazing as nearly 500 masons attended. The Lodge was opened on the Entered Apprentice degree, so that all Masons could attend. Most of us were dressed in our full scout uniforms. Introductions were made and the wealth of Masonic knowledge in the room was impressive. Numerous Masters and Past Masters, 3-4 past state Grand Masters, heads of Scottish Rite and York Rite bodies, etc.

In his career, West was instrumental in the early Scouts being a strong champion for it on many fronts, building its acceptance and credibility to many groups including the unions who disliked its early anti organizing language and with the Catholic Church (which at first prohibited membership because of its non Catholic start with the protestant YMCA).

Looking beyond Beards contribution and West’s obvious affiliations to Masonry, another possible Masonic connection to the Boy Scouts comes in Baden-Powell himself.

Much has been written on this subject, and its easy to find many references that say that Baden-Powell was NOT a Freemason (including a letter from then UGLE Secretary J. MacDonald in 1990) , and that the Scouts were in no way a Masonic club for boys.

Despite the similarities between the two and the obvious awards and rank progression it is possible, however, to find a small connection to Baden-Powell and Masonry through Rudyard Kipling, who, as many readers will know, was a very prolific Mason and who took his Masonry very seriously in both his works of fiction (See the The Man Who Would Be King

Despite the similarities between the two and the obvious awards and rank progression it is possible, however, to find a small connection to Baden-Powell and Masonry through Rudyard Kipling, who, as many readers will know, was a very prolific Mason and who took his Masonry very seriously in both his works of fiction (See the The Man Who Would Be King film and its original book) and in his poetry (see The Mother Lodge). Baden-Powell and Kipling were very much associated from their initial friendship which developed somewhere between 1882 and 1884 in Lahare, India. Its doubtful to say that the friendship led to a Masonry based civic organization for boys, but its possible to see how through conversation and comparison some elements might have been wound together, especially as you read more extensively into their friendship which continued for many years until their passing.

Further, its more likely to see how the spirit of the age contributed to the early Scouting movement, especially as youth orders seemed to lend themselves to more grown up responsibilities expressed, in some measure, through the Scout Defense corps (or even perhaps in the more nefarious Hitler Youth which existed from 1922 to 1945, the Young

Soviet Pioneers from 1922 – 1991, or even more alarming the American Boy Scouts which was a parallel of the Boy Scouts of America which existed from 1910-1920 and organized as a more militaristic program to train boys). A bolder aspect of this ideal of civic citizen contribution can perhaps be seen in the Civil Conservation Corps which had a two fold aspect of building the well-being of the country and putting unemployed men to work. In that same period there was a growing sense of losing the youth to the changing society, and the Boy Scouts were an early precognition of just how important it was to keep the youth engaged and conscious to civic involvement. In the years following the BSA incorporation, Eleanor Roosevelt was a champion for youth engagement as she championed in 1930 the American Youth Congress which saw, then as now, the need to engage youth and instill values.

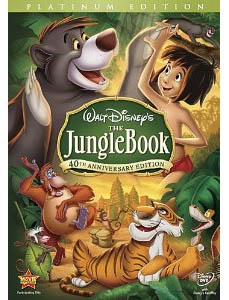

But, from the relationship of Baden-Powell and Kipling, and this spirit of the age, came the essence of what would become the Cub Scouts taking shape from Kipling’s work “The Jungle Book

But, from the relationship of Baden-Powell and Kipling, and this spirit of the age, came the essence of what would become the Cub Scouts taking shape from Kipling’s work “The Jungle Book” (see both the Film The and the Book). The Wolf Cubs, as Baden-Powell had styled them, felt that the Jungle Book was every bit suitable to the idea of youth scouting. Kipling was in such agreement that he even contributed much of his Jungle Book to it including the exact method of the Wolf Cub howl instructing its call as:

“A-KAY-Lar with an accent on the second syllable which can be prolonged indefinitely. The initial A on the other hand is almost a grunt – ‘Er’- Try this and you will see the beauty of the thing.”

Some other notable elements from The Jungle book that made there way into the Cub Scouts include “Law of the Pack,” “Akela,” “Wolf Cub,” “grand howl,” “den,” and “pack” all (and more) used with Kipling’s blessing.

See the History of Cub Scouting for a time line of its formation up to its 75th anniversary in 2005.

The obvious connections mentioned above, Freemasonry and the Boy Scouts have a few other traces in common. Besides the obvious interaction of Masons in the ranks of the Scouts, its been suggested that the Order of the Arrow, created in 1915, is a Masonic ritual embedded into the Boy Scout organization.

Created by E. Uner Goodman and Carroll Edison, the two collaborated to make a club within the club – to create a camp fraternity to improve the Scout’s summer camp experience.

From Wikipedia:

Goodman and Edson decided that a “camp fraternity” was the way to improve the summer camp experience and to keep the older boys coming back. In developing this program they borrowed from the traditions and practices of several other organizations. Edward Cave’s Boy’s Camp Book was consulted for the concept of a camp society that would perpetuate camp traditions. College fraternities were also influential for their concepts of brotherhood and rituals, and the idea of new members pledging themselves to the new organization. Ernest Thompson Seton’s Woodcraft Indians program was also consulted for its use of American Indian lore to make the organization interesting and appealing to youth. Other influences include the Brotherhood of Andrew and Phillip, a Presbyterian church youth group with which Goodman had been involved as a young man, and Freemasonry. The traditions and rituals of the latter contributed more to the basic structure of the rituals than any other organization. In an interview with Edson during his later years, he recalled that the task of writing the first rituals of the society was assigned to an early member who was “a 32nd degree Mason.” Familiar terms such as “lodge” and “obligation,” were borrowed from Masonic practice, as were some ceremonial practices. Even the early national meeting was called a “Grand Lodge,” thought to be a Masonic reference. Goodman became a Mason only after the OA was established.

Goodman was Raised in Lamberton Lodge No. 487, Philadelphia, Pa. about 1917 according to Denslow’s 10,000 Famous Freemasons.

The aim of the order of the arrow is to allow Scouts to choose from among their numbers the individual who best exemplifies the ideals of Scouting. Those selected are to embody a spirit of unselfish service and brotherhood.

Goodman said of it:

“The Order of the Arrow is a ‘thing of the spirit’ rather than of mechanics. Organization, operational procedure, and paraphernalia are necessary in any large and growing movement, but they are not what count in the end. The things of the spirit count: Brotherhood, in a day when there is too much hatred at home and abroad; Cheerfulness, in a day when the pessimists have the floor; Service, in a day when millions are interested only in getting or grasping rather than giving.”

From the other side of the threshold there are some Masonic Grand Lodges that recognize cross over clubs like the National Association of Masonic Scouters and promotes a greater level of interactivity with troops. The most significant interactions with Freemasonry today, however, are those Masons with sons who have served in some capacity in the leadership of their Troop or Local Council.

From the other side of the threshold there are some Masonic Grand Lodges that recognize cross over clubs like the National Association of Masonic Scouters and promotes a greater level of interactivity with troops. The most significant interactions with Freemasonry today, however, are those Masons with sons who have served in some capacity in the leadership of their Troop or Local Council.

Freemasonry does not rank in the top 10 of organizations that support the Scouts (the top 5 being the LDS Church, the Methodist Church, the Roman Catholic Church, PTA Groups, and private citizen groups) which is a terrible missed opportunity for lodges to engage and support an organization in such affinity to its own ideals. The reason for this I can only extrapolate is that Scouting is perceived to encroach on its own membership from participating in DeMolay, the Masonic youth order, founded in 1919.

With this briefest glimpse at the Scouts origins, the next step is to look at its organization to appreciate its flexible and member friendly approach to put the priority on the Scouter and less on the place the Scouts practice.